A journey in brewing a nearly-authentic Finnish sahti in the Seattle area.

Fermentation and Cold Conditioning

Thankfully, fermentation went off without a hitch. Every couple of days, I checked the gravity of each sahti with a refractometer. From some advice I received online from other brewers, once one of the fermenters reached a reading of about 1.034-1.038, I moved it into my kegerator just above 35°F for cold-conditioning. There, fermentation would continue more slowly, and I expected the gravity would drop a few more points. Checking final gravity with a hydrometer, I discovered that the Jovaru and Lutra attenuated much further than the weizen yeast.

Target OG: 1.100

Actual OG: 1.075

Jovaru FG: 1.021 (7.1% ABV)

Lutra FG: 1.021 (7.1% ABV)

Weizen FG: 1.035 (5.3% ABV)

After about 10 days of cold-conditioning, I transferred the sahti off their yeast beds and into growlers, capped them, and returned them to the kegerator. There, they would live until fully consumed, to avoid spoilage. To drink the sahti, I would just open up a growler, pour a glass, then put the growler back. I’ve never treated beer like fresh milk or juice before!

Final Impressions

Regretfully, I don’t appear to have taken a single photo of the beer. I literally don’t understand how this never happened. So I’ll describe it for you.

The color was brown to ruby-brown, with a light amount of carbonation when pouring into the glass. Nearly identical appearance for all three. There was not much of a head or foam on top. The aroma was malty, sweet and roasted. The flavor differences from the yeast were quite perceptible, but none of the three tasted like a completely different beer to me.

The Lutra kveik sahti had more of a citrus character, whereas the Jovaru farmhouse sahti had more of a dark fruit or apricot character. The weizen sahti was full of banana flavor, which ended up being my favorite.

They were all very sweet but didn’t taste unfinished. I’ve had some experiences with incomplete fermentation before, in combination with under-carbonation, and the result was a cloying, syrupy mess that was nearly impossible to drink. This was not that, and it was easy to have a glass or two at a time. I was also surprised to find there was very little alcohol burn. For a medium-high strength beer, it went down smoothly.

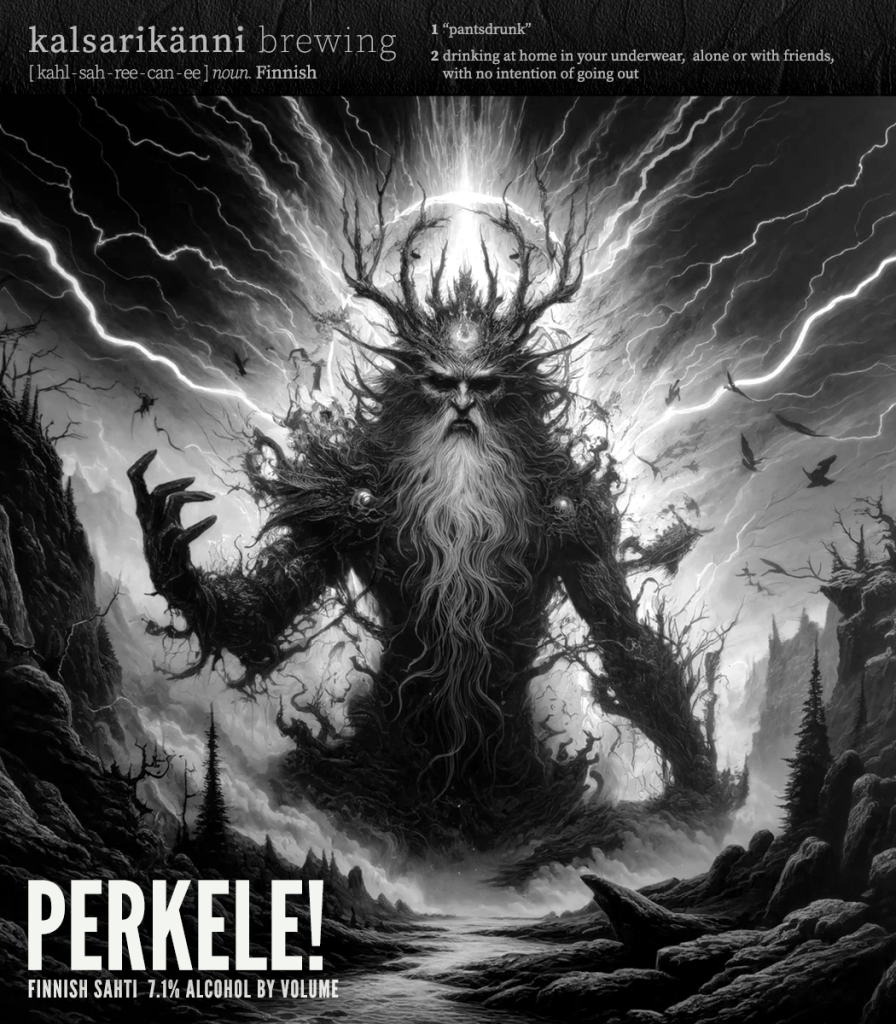

The Label

Lately, I’ve been exploring using generative AI in Photoshop to help design my own labels. I must admit this is more of a morbid curiosity, like a “know-your-enemy” type thing. I’m not a big fan of the AI hype that is disrupting the job market right now. It feels marginally okay to use it for my own personal projects, if only to better understand how it works and what it is capable of. But this might be my last time using it.

All that said, after significant back-and-forth prompting to refine the design (it never just works without a human to fix mistakes and corral its efforts), I’m very happy with how this one turned out.

It looks awesome:

Next Time

I will brew another sahti again soon!

I still have plenty of malt left, and I harvested the yeast from this batch so I can reuse it. The next time around, I will be more careful with staying under the limits of my brewing system. I might also try brew-in-a-bag to allow for more grain in the kettle. Now that I have a properly functioning pH meter and recirculation pump, I think it’ll be a much more enjoyable experience. For the yeast, I might do another split-batch and try to source some fresh baker’s yeast from a local grocery or bakery. It won’t be Suomen Hiiva brand, but I’m curious what difference it would make.

I also discovered there are so many different kinds of sahti: light-colored sahti, rye sahti, smoked sahti, sour sahti — and many others. It seems like you could do whatever you want. I’m very excited to try brewing more of these, each time feeling more deeply connected to a truly fascinating and special tradition.

Leave a Reply